Lesson 3: Principles of Zen Shiatsu

Bodywork

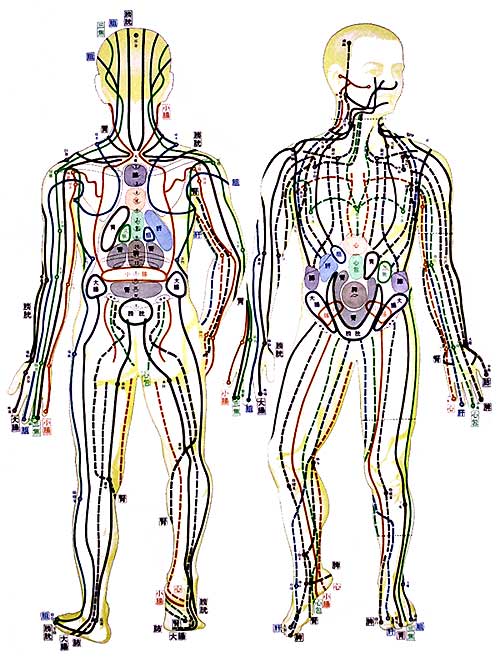

Consistent with the basic concepts of Traditional

Chinese medicine, Zen Shiatsu is grounded in that health theory that health

problems are attributed to or involve:

- imbalances of yin and yang

- disharmonies between the internal organs

- blockages of the circulation of ki (in

Chinese: qi; in English: chi) through the meridians

The unique features of Zen Shiatsu, compared to Traditional Chinese medicine

techniques such as acupuncture or other shiatsu techniques, are these:

- For diagnosis, abdominal palpation is the primary technique used. Abdominal

diagnosis (in Japan: hara diagnosis) is an ancient Chinese technique

that had been largely abandoned in China, but became important of Kampo

(the Japanese practice of Chinese medicine) around the beginning of the

18th century. Abdominal diagnosis is used in Japan for herbal medicine prescribing,

acupuncture, and Zen Shiatsu. The diagnosis is primarily aimed at determining

whether each meridian is relatively empty (Japanese: kyo, Chinese:

xu) or relatively full (Japanese: jitsu; Chinese: shi).

At the end of each treatment the abdominal diagnosis is performed again

to ascertain improvements that have occurred.

Alex Holland President

and Founder, Asian Institute of Medical Studies

Ask a Zen Shiatsu question

- Pressure is applied at intervals along the meridians that were described

by Masunaga. He presented 12 meridians, corresponding to the 12 basic

organ-affiliated meridians of the Chinese system. The meridian pathways are

similar to, but not the same as, the Chinese ones; the main difference being

an extension of each meridian to a range from legs to arms, passing through

the associated diagnostic region of the abdomen.

- The treatment involves brief contact with each point, in a somewhat

rhythmic pattern as a portion of a meridian is traced. The contact is with

fairly strong pressure that is applied using the movement of the practioneer

body, fingers, elbows, and other parts of the body.

- To attain the proper combination of pressure and movement along the

meridian, the practioneer may move frequently around the recipient's body and

may even move the recipient (who is instructed to remain passive), such as

lifting the head or arms. The actions may include turning or bending over the

recipients body parts with the purposes of gaining access to essential points,

stretching the meridians, and using gravity or leverage to attain the needed

pressure at certain points. The therapy does not focus on one part of the

body, even if the health problem is localized; the whole body becomes

involved.

- The practioneer works within a meditative state, focusing on the responses

of the recipient so as to properly direct the therapy, as opposed to focusing

on selection of pressure points by a theoretical

system. To develop this condition of heightened awareness and clear

intention, the practioneer practices meditation regularly.

Because of its connection to Traditional Chinese Medicine, Zen Shiatsu serves

as an excellent adjunct to acupuncture therapy as well as Chinese or Japanese

herb prescribing, fitting well with the theoretical framework. Further, it

serves as a complementary therapy for Western methods of manipulation, including

chiropractic or standard massage (e.g., Swedish style), providing an entirely

different stimulus to the body.

Although Masunaga's Zen Shiatsu is considered essential reading for practioneer,

the main textbook of Zen Shiatsu used today is Shiatsu Theory and Practice

by Carola Beresford-Cooke (first published 1996; revised edition 2002). She

has outlined five basic principles of Zen Shiatsu as follows:

- Relax The practioneer must be in a comfortable physical and mental

condition to convey comfort to the recipient; the arms, hands, neck, and

shoulders must be relaxed, not tensed, to give the proper treatment and to

perceive the recipient responses.

- Use penetration rather than pressure. It is understood that the body has

spots (called tsubo) that can receive the pressing by the practioneer;

the muscle gives way to the penetrating force to let it enter, rather than

being pushed away by pressure. The result is an entirely different experience

than the mere finger-pressing, and requires that the practioneer have the

correct position in relation to the recipient and be mindful of the technique

being used.

- Perpendicular penetration without side-to-side motion. Unlike many massage

techniques where movement across the surface is emphasized, Zen Shiatsu

involves penetration at each point, perpendicular to the body surface.

Although there are a few exceptions, the treatment does not involve rotations,

back-and-forth, or wiggling movements of the hands, but simple direct

inward-directed movements.

- Two handed connectedness. The Zen Shiatsu practioneer maintains two hands

on the recipients body; one hand may be still and holding a part of the body

in position, while the other is active, penetrating points on the meridians.

The practioneer is advised to give attention to the role of both hands, not

just the mode active one.

- Meridian continuity. The focus of the therapy is to treat an entire

meridian, not just individual points or regions. This is based on the theory

that the imbalances to be addressed are based in the meridians, which require

a free flow of ki throughout.